Entrepreneur Cases Signal EB-5 Eligibility Challenges for Small Businesses (Vol. 2, Issue 3, October, 2014 , pgs. 30-32)

by Lincoln Stone and Taiyyeba Safri Skomra

Experience teaches that entrepreneurs and sole proprietors in small business have unique challenges in qualifying for the EB-5 category. Many of these applicants are seeking permanent residence in the EB-5 category after having operated a small business while in the United States in E-2 treaty investor status. A fair share of the problems encountered by entrepreneurs in seeking EB-5 based residence stems from incorrect assumptions about what constitutes investment in the eyes of the USCIS examiner. These problems exist for entrepreneurs whether the case involves a lone EB-5 investor or multiple investors claiming the new commercial enterprise (“NCE”) will employ all the required personnel as employees of the NCE, or on the other hand the NCE is affiliated with a regional center thus also enabling the credit of indirect jobs. Entrepreneurs may find that a successful EB-5 case requires reevaluating the company’s capital structure, taking a much harder look at how it employs personnel, and overhauling its bookkeeping and recordkeeping. Some articulation of the problems entrepreneurs routinely encounter in connecting “incremental investments” with incremental job creation is found in S. Pilcher, “Preserving the EB-5 Option for the Entrepreneur: Strategic Considerations for Startup Counsel,” Immigration Options for Investors & Entrepreneurs (AILA 2014).

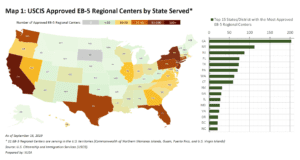

Small businesses also seem to attract much higher scrutiny from USCIS examiners. Most denials of EB-5 petitions filed by investors in small business involve an examiner finding inconsistencies in documentation. Essentially the examiner locks in on a discrepancy, or several of them, and then uses the discrepancy to discredit the core factual claims advanced by the petitioner. Often, it seems, the discrepancy results from the incorrect assumptions made by the investor and from sloppy record-keeping. Considering that well more than 90% of all EB-5 petitions are filed by investors in regional center-affiliated NCEs, more frequently involving institutional parties, high-quality documentation, and well-structured capital investments, the entrepreneur’s EB-5 petition based on a small business investment needs to be exhaustively vetted prior to filing with USCIS.

Recent non-precedent decisions of the Ad-ministrative Appeals Office (“AAO”) illustrate the difficulties facing entrepreneurs in preparing EB-5 cases. We reviewed dozens of AAO decisions posted to the USCIS website. Here we summarize key aspects of these cases.

Proof of Investment

In one case the petitioner had invested in the NCE for purposes of developing housewares for the wholesale market. The main problem in the case centered on the fact there was a shareholder loan of $30,250 and the entrepreneur claimed he had repaid that loan as part of a later $100,000 deposit to the NCE. The petitioner expected USCIS to figure out that the deposit constituted part repayment of the loan and part equity investment, not-withstanding the confusion of various documents including corporate minutes of meetings, three sets of stock ledgers, and the lack of corroboration in the corporate income tax return. USCIS homed in on the “inconsistencies” that were not resolved. The AAO also found that the petitioner failed to meet his burden where there were two separate deposits of $520,000 each, one by an unrelated entity and one by the petitioner, followed by a withdrawal of $520,000, without clarification of whether it was the petitioner or the entity that was repaid.

In another case, the NCE was a seller of popular brands of used cars and a provider of long-term financing to its customers. The entrepreneur claimed to invest more than $2.1 million in the NCE. The AAO rejected the contention that $489,000 of “purchased assets” should be counted as the investment, finding the evidence unconvincing on whether it was the petitioner rather than the NCE that bought the assets. The AAO also declared that shareholder loans of $580,000 appearing on one NCE income tax return could not be merely swept aside by a later NCE income tax return, without proof that the later return had been filed with IRS and the earlier “erroneous” returns had been amended and corrected. The AAO also found that “income receivables” of $1.2 million could not be credited as investment because they are a form of “retained earnings” that cannot be considered qualifying investment. Finally, the AAO noted that photocopied deposit slips accounting for more than $1.4 million could not be credited as petitioner’s investment because the handwritten notations were self-serving and not reliable.

Several AAO decisions illustrate that entrepreneurs need to be alert to what appears to be the “fraud antenna” in USCIS review of small business cases. In a case where a sublease was submitted as proof of investment and the site of business operations, USCIS seized on the indicated total rentable area (11,044 square feet) instead of the actual leased area (375 square feet), and also noted that there was conflicting documentation as to the exact location of the business (on the 3rd floor or the 4th floor). The sizable discrepancy and open questions led to a site visit by USCIS. The AAO agreed with the Director’s finding that submission of the false sublease constituted material misrepresentation.

Entrepreneurs need to be especially careful about submitting multiple petitions in an effort to correct past mistakes. These corrective filings might accomplish nothing more than provide damning evidence of inconsistent statements. One entrepreneur who established a Chinese restaurant filed two I-526 petitions a year-and-a-half apart with inconsistent statements as to the timing and amount of initial investment and the total investment. His employment and residential history also conflicted with information in other filings made with USCIS, calling into question his claims of managing and operating the NCE. The AAO concluded these unresolved inconsistencies rose to the level of willful and material misrepresentation, and warned: “This finding of misrepresentation shall be considered in any future proceeding where admissibility is an issue.” As a consequence, the entrepreneur is permanently barred from entering the United States, unless there is a citizen or legally resident family member to support a waiver grounded in abundant evidence of extreme hardship to the relative.

Note that many of the cases that have problems with proof of investment also suffer from insufficient evidence of lawful source of funds. However, we recognize the source of funds topic is best addressed separately. One resource on the topic is: E. Arias, “Documenting an EB-5 Investor’s Source of Funds – Including Practical Tips and Review of Recent RFE Trends,” Immigration Options for Investors & Entrepreneurs (AILA 2014).

Capital At Risk

Even if USCIS does not challenge that the entrepreneur invested capital, there are other hurdles. In one case involving one of three EB-5 investors who joint ventured to fund the development, ground-up construction, and management of an assisted living facility, USCIS denied the petition for the lack of evidence of the $2 million funding the NCE required from a lender. The AAO affirmed, noting the belated evidence of such funding did not cure the fact that the funding source was not available at the time of I-526 petition filing. The AAO also declared that the mere assignment of a contract to purchase land and nominal expenditures for a market study were insufficient business activity to place the EB-5 capital at risk of loss. Finally, the commitment by the limited partnership to pay the limited partners five years after making their capital contributions was an impermissible redemption under Matter of Izummi, which could not be rectified by a later post-filing agreement to amend the partnership agreement.

In yet another case, where the NCE imported and distributed Filipino products throughout the United States, and had been conducting US business for nine years and was slightly profitable, the AAO held that the petitioner’s capital investment was not at risk. The AAO reasoned that the entrepreneur should explain why an already-profitable business would need an infusion of capital. This rationale was elaborated on in a similar case involving a NCE that exported sea cucumbers to Asia. The AAO stated that where there already existed a slightly profitable business and there is no expansion plan and no indication of what the EB-5 capital investment would be used for, there is no at risk investment. The AAO dismissed the business plan that provided for future job creation because the business plan lacked any justification for hiring. The AAO also ridiculed the confused organization charts, job titles, job descriptions, and timeline for hiring.

Job Creation

The AAO reminds us that the touchstone of a reliable comprehensive business plan that satisfies Matter of Ho is one that is reasonable and credible. The plan for job creation should not be merely conclusory and wishful. In the housewares case reviewed above the AAO concluded that the plan for hiring 17 workers was not credible without addressing the relevant competitive market and demand for products.

In a case involving a manufacturer of automotive parts for enhancing automotive performance, the AAO observed a common problem in EB-5 cases involving a pre-existing business, namely, overstating the number of qualifying positions that have been created. The entrepreneur needs to be absolutely clear about how many employees exist prior to investment, and how many have been created thereafter, and then the business plan must document well how many more full-time positions will be created within 2.5 years of USCIS adjudication of the I-526 petition. Meaning, if the business plan projects a total of 18 full-time positions, and the entrepreneur is thinking that is ten more than the eight employees he had prior to investment, this could be faulty reasoning. USCIS may downsize the number of positions already created (and thus the total created) by identifying them as part-time or filled by non immigrants and consequently not to be credited for EB-5 purposes

Indeed, in the used cars case referenced above, as if the investor were unaware of the existence of EB-5 regulations, the AAO remarked that the petitioner and immediate family do not count, nonimmigrant visa holders do not get credited, independent contractors are not relevant, nor are part-timers. And, above all else, employees should be documented with reliable I-9s and paystubs showing the number of hours worked.

Entrepreneurs and Regional Centers

Not all regional center-related EB-5 cases involve massive amounts of capital invested by dozens of investors who have relatively minimal participation in the NCE. Occasionally, entrepreneurs do associate with regional centers. The posted AAO cases include several regional center-based EB-5 petitions involving relatively small businesses. In one case where the NCE would fund the development, production, manufacture and sale of alcoholic gelatin shots, the AAO declared that job creation estimates must be based on market estimates and market data indicating that the assumptions of the job creation methodology are reasonable. Both the business plan and economic impact analysis relied upon in the I-526 petition were dated in 2012, more than two years after USCIS had approved the regional center. In view of the fact the petitioner did not argue to the AAO that either document had been reviewed by USCIS as part of the regional center proposal, the AAO cited to the May 2013 EB-5 Policy Memo and concluded “USCIS need not afford either document deference.”

Exactly what USCIS approves or does not approve in its regional center approval letters is a subject touched upon in two other AAO cases. In one regional center case involving EB-5 capital to fund a manufacturing facility in Florida, the AAO noted that a regional center amendment indicated an investment focus on manufacturing of steel frame buildings. The petitioner contended that the I-526 petition and regional center amendment proposal were based on the same business plan and economic analysis. The Director had stated that the business plan had been materially changed, but without explanation. The AAO remanded the case so that the Investor Program Office could make an “initial assessment as to whether the business plan, the business plan addendum, and the economic impact analysis in the record should be afforded deference.” Evaluation of material change is ripe, it declared, only after a determination on deference is made.

In a case with a similar outcome, involving EB-5 investment in a marina in Florida, the AAO framed the issue on appeal as follows: If the regional center proposal approved by USCIS in October 2010 included a comprehensive business plan compliant with Matter of Ho, “then that business plan and the accompanying economic impact analysis should be afforded deference.” The petitioner contended the I-526 petition used the same methodology and multipliers as presented in the regional center proposal. Because the Director had denied the I-526 petition without analyzing the question of deference, the AAO remanded the case to determine whether any of the economic impact analyses in the record should be afforded deference.

These deference decisions bring to mind still another regional center-linked case where prior USCIS “mistake” in approving a regional center amendment and in approving related I-526 peti-tions (i.e., multiple mistakes) was used as the rationale to kill the project. It signals the next chapter in the 20 year-evolution of the regional center approval letters. (For background see L. Stone, Trends in Approvals of Regional Centers (

RCBJ, May 2013); S. Lazicki, 2013 Regional Center Approval Letters (

RCBJ, June 2014). To say that a regional center approval letter is binding in some sense on USCIS examiners in related adjudications of I-526 petitions, and to frame that in the language of the USCIS deference policy, is to ignore the near-limitless bounds of the exceptions for mistake and material change. USCIS is making long strides in formalizing its regional center approval letters. But to make two categories of regional center approval letters, one for hypothetical projects and another for actual projects, is not to answer all the lingering questions these letters have created. Until there is a lot more clarity, lone entrepreneurs and pooled investors in major EB-5 projects are likely to be wrestling with USCIS for the foreseeable future over what a regional center approval letter actually means in terms of predictability. ■

RCBJ Retrospective articles are reprinted from IIUSA’s Regional Center Business Journal trade magazine. Opinions expressed within these articles do not necessarily represent the views of IIUSA and are provided for educational purposes.