This is a member perspective and the views of the author are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views or position of IIUSA. This blog was originally published Wolfsdorf Rosenthal LLP, an IIUSA Member, on August 20, 2020. See Here.

By Joseph Barnett, Partner, Wolfsdorf Rosenthal LLP

Mr. Barnett is a Partner at Wolfsdorf Rosenthal LLP and a member of the IIUSA Editorial Committee

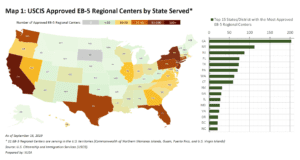

Invest in the USA, the national industry trade association for the EB-5 Regional Center Program, recently secured over 500 pages of EB-5 adjudicator training materials from USCIS’ Immigrant Investor Program Office (IPO) through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit. IIUSA will be receiving nearly 2,000 pages of documents in total over the next few months as a result of the FOIA litigation, so expect another blog when released and reviewed. While these May 2019 materials precede the November 2019 EB-5 regulations, they still provide valuable understanding of USCIS’ adjudication policy. Here are some insights from these materials.

Purchase of Existing Business Incorporated After November 29, 1990. The training materials confirm a plain reading of the regulations at 8 C.F.R. § 204.6(h)(i): If a business was incorporated or organized after 11/29/1990, a “new commercial enterprise” has been established. Even if the petitioner purchased or expanded the existing business, IPO need not separately examine the business to determine whether the restructuring/reorganization or substantial change requirements at 8 C.F.R. §§ 204.6(h) (ii)-(iii) have been met. While this appears straightforward, in practice, adjudicators appear to mix up the requirements for these types of EB-5 cases, so investors should proceed cautiously.

Bridge Financing Nexus. In general, USCIS does not permit EB-5 funds to be used to simply refinance an existing (long-term) loan because, in those instances, the EB-5 capital is repaying other money that has already been spent and that has already created jobs which are not attributable to a petitioner’s capital. USCIS’ bridge financing policy was crafted by the agency as a narrow exception to this disallowance. USCIS must find a “nexus” between the initial bridge financing and contemplation of using subsequent money to replace it to get credit for new job creation. The training materials state this contemplation can be evidenced in the initial transaction documents and the business plan submitted for the Form I-526. USCIS adjudicators will look at “the terms of the purported bridge loan financing in relation to the larger project and the bridge loan’s interim nature,” including total amount financed, possible higher interest rates, and express acknowledgements of interim nature in loan documents.

Material Change. The training materials note that material change can involve any eligibility requirement at the Form I-526 stage and that the initial question is whether the petitioner was eligible at the time of filing. The materials cite Kungys v. United States, 485 U.S. 7 59, 770-72 (1988) for the proposition that a change in fact is material if the changed circumstances would have a natural tendency to influence or are predictably capable of affecting the decision. Most notably for redeployment purposes, the materials state that “documents may generally be amended to remove such a provision in order to allow the NCE to continue to operate through the RC immigrant investor’s period of condition permanent residence.” The materials distinguish between ‘conforming amendments” to correct inconsistencies and amended/eliminated provisions to which USCIS has objected and state that adjudicators should check and rely on “open source” to provide evidence of material changes to a petition.

Deference. The training materials include a detailed discussion of “exceptions to deference” – when the underlying facts upon which a favorable decision was made have materially changed, when there is evidence of fraud or misrepresentation, or when the previously favorable decision is determined to be legally deficient. USCIS notes that a document that supports a determination of eligibility for one application or petition at one point in time may not support a determination of eligibility for another application or petition at another point in time (for example, when an initial review of a project occurred/approved in 2016 with a timeline of project work to be completed by 2017, and a new filing in 2019 is submitted when a google search shows project has yet to be started).

Indebtedness. The materials note the Zhang Class Action case from November 2017, where the United States District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that the USCIS’ reading of the definition of capital at 8 C.F.R. 204.6( e) to require that loan proceeds from indebtedness be treated as indebtedness ( and secured by assets of the petitioner) was “plainly erroneous. USCIS states that it is planning to appeal this decision but has immediately began undertaking steps to implement the court’s order.

Escrow. The training documents include a number of problematic escrow release provisions. One common one – when funds will be set aside in escrow-to refund a Petitioner’s denied I-526 but no provisions to contribute the funds to NCE upon 1-526 approval and/or visa issuance and admission to the United States as a conditional permanent resident, or approval of the investor’s Form I-485, undermining the petitioner’s ability to show an actively in the process of invested the required amount of capital. It also appears that when adjudicators spot the potential for loss which could erode a petitioner’s capital below the required investment amount, they are to elevate the case to a branch chief and/or division chief for guidance.