Losing your Attorney-Client Confidentiality in EB-5

Losing your Attorney-Client Confidentiality in EB-5

by Michael G. Homeier, Founding Shareholder Homeier & Law, P.C.

In “The Case of the Misguided Model,” famous TV attorney Perry Mason’s client confesses that he killed a man. When another man is charged with the murder, our hero Perry is torn between his professional duty as an officer of the court, his moral duty to prevent injustice, and his ethical duty to maintain his client’s confidences.

Perry’s ethical predicament flows directly from the attorney-client confidentiality privilege, long-enshrined as perhaps the most salient testimonial privilege existing under the Anglo-American legal system (and classic American television shows). The privilege protects the confidentiality of communications between clients and their attorneys from compelled disclosure in an evidentiary proceeding. Additionally, the rules of ethics governing the legal profession in every state (exemplified by ABA Model Rule 1.6) reflect the even broader principle that an attorney’s duty to maintain client confidentiality extends to all information in the attorney’s possession that is related to the representation. However, a lawful device now being actively deployed, including in the EB-5 industry, can effectively void the privilege, strip confidentiality from information and documents, and render attorney-client communications and files accessible by people other than clients and their lawyers.

The attorney-client privilege has long been defined along the following lines:

The attorney-client privilege … authorizes a client to refuse to disclose, and to prevent others from disclosing, information communicated in confidence to the attorney and legal advice received in return. The objective of the privilege is to enhance the value which society places upon legal representation by assuring the client the opportunity for full disclosure to the attorney unfettered by fear that others will be informed. … While the privilege belongs only to the client, the attorney is professionally obligated to claim it on his client’s behalf whenever the opportunity arises unless he has been instructed otherwise by the client.

Glade v. Superior Court, 76 Cal.App.3d 738, 743 (1978) (citations omitted).

The attorney cannot be compelled to disclose information related in confidence by the client, nor may the client be forced to disclose information communicated to the attorney. Similarly, the attorney is not permitted to voluntarily disclose client communications on his own initiative, because the privilege belongs to (is “held by”) the client. Further, information not technically within the scope of the testimonial privilege may nonetheless be protected from disclosure by the attorney’s ethical obligations to the client.

The device that effectively guts the attorney-client privilege and client confidentiality is the appointment of a “receiver.”

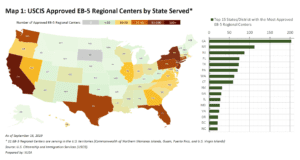

A receivership is a provisional remedy under which the authority to control and operate a business or institution is vested in an outside person called a “receiver,” often appointed by a court during litigation or enforcement proceedings, who is given custody of and made responsible to protect and manage the property of others and to prevent waste or theft of property or assets, often by taking legal action. See, http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/receiver. Receivers are often used in bankruptcy cases, as an obvious example. They are also prevalent in securities fraud litigation cases, including those in the EB-5 industry. The vast majority of SEC enforcement actions brought in the EB-5 industry where fraud is alleged and substantial assets belonging to immigrant investors remain vulnerable, have been accompanied by the SEC seeking the appointment of a receiver by the court to take over control of the wrongdoing business and prevent further theft or waste. See, e.g., http://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/31574/20160415/jay-peak-resort-taken-over-by-federal-receiver-amid-alleged-investment-fraud.

How does appointment of a receiver lead to the effective gutting of attorney-client confidentiality?

The testimonial privilege applies both to natural persons, as well as to business entities, which are artificial persons established by law and which act through individuals representing the entity, such as officers, managers, or employees. Broadly speaking, in a corporate context, if the acts of the individual that are the subject of legal action were performed for (on behalf of) the entity as the acts of the entity, then it is the entity that is the client rather than the individual in his or her personal capacity—and therefore the privilege belongs to the entity.

Since the client, and not the attorney, holds the privilege, the client alone has the right to assert it or waive it. When the client is an entity, the entity’s privilege is exercisable by management (a manager or managing member of an LLC, or the general partner(s) of a limited partnership). All communications between the entity’s management and its attorneys (including corporate lawyers, immigration lawyers, and securities lawyers), are privileged—the confidentiality of these communications cannot be breached without the client’s assent (or waiver). However, if and when there is a change in the entity’s control, while the privilege remains held by the entity, its exercise passes to the successor managers; it does not remain with the former management themselves. Instead, the new managers may waive the privilege, and require that all previous communications between prior management and counsel be provided to new management. Similarly, new management also controls the extent to which non-privileged but confidential information related to the attorney’s representation of the client may (or must) be disclosed.

Quoting directly from a receiver letter demanding copies of confidential communications:

[T]he Receiver is authorized, empowered and directed to have access to and to collect and take custody, control, possession, and charge of all assets and records of the Receivership Entities and their subsidiaries and affiliates. [B]y operation of law and by virtue of his appointment, the Receiver succeeds as legal representative to the Receivership Entities, with exclusive authority and control over their assets, including their books, records, and assets. [Citations omitted.]

The receiver thereupon demanded “turnover [of] all files and documents… pertaining to any matter you or your firm have handled for any of the Receivership Entities.” Essentially, the receiver is new management, able to waive the attorney-client privilege or duty to maintain confidentiality existing between the entity’s counsel and the entity’s prior management. As a result, confidentiality of the previous communications between the entity and counsel can no longer be maintained, and the receiver can review all of those communications.

The SEC has sought the appointment of a receiver to assume control of defendant entities (both new commercial enterprises and job creating entities, and their affiliates) and their assets in almost all of its EB-5 enforcement actions, starting with the Chicago Convention Center case in 2013, and continuing through its most recent, 2016’s Jay Peak case (just as the SEC does in its non-EB-5 actions). Going forward, the pattern is likely to continue, whenever the SEC believes investor funds are at risk. And unlike Perry Mason’s hapless opponent, District Attorney Hamilton Burger, in such cases the government usually prevails.

Accordingly, EB-5 entities cannot presume that their communications with counsel will remain privileged and confidential in all circumstances, in particular in any case where a receiver may be appointed.