IIUSA Executive Director, Aaron Grau, recently provider a reader of the Investment Migration Insider with a lesson on the U.S. legislative process and how various terminology applies to the EB-5 Regional Center reauthorization efforts. It is our hope that the article provides some much-needed clarity as investors and stakeholders try to better understand the many moving parts.

If you are an industry stakeholder and not yet a member of IIUSA we encourage you to join today! Your contribution would enable IIUSA to more effectively advocate for the industry reauthorization and provide you access to a host of business development opportunities in the year ahead!

Originally Published in Investment Migration Insider

by Aaron Grau, Executive Director, IIUSA

Invest in the USA (IIUSA) always does its best to provide legislative updates, information, and answers to anyone who asks. Sometimes we field inquiries about policy; the validity or wisdom of EB-5 investment amounts or whether good faith investors can rely on being “grandfathered” into the EB-5 system in the event of another lapse. Sometimes we address concerns about politics; whether policy makers are prioritizing EB-5 reauthorization or the best way to communicate with a Member of Congress or Senate staff. Lately, however, the questions are not about policy or politics. They are about procedure. What do “budget reconciliations,” “continuing resolutions,” “omnibuses,” and “minibuses” all mean to the future of EB-5? As with most things, the answer is not straight-forward, but I hope this explanation helps.

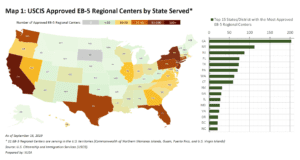

The bill to reestablish the EB-5 Regional Center program is too small and arguably too controversial to survive the entire legislative process on its own. The EB-5 community came as close as it ever had to seeing that possibility through and in the final minutes before a Senate vote the effort failed. Therefore, the bill must be attached to some bigger legislation whose failure has more dire consequences.

Typically, these “must pass” bills support U.S. government functions writ large, like the annually passed National Defense Authorization Act or any one of the 13 appropriation bills that provide funding to all the federal agencies including, but not limited to the U.S. Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, Defense, Labor, Energy, and Homeland Security. If any one of these 13 bills do not become law by the end of the U.S. fiscal year (September 30th), the agencies it supports simply shut down. If none of them pass, the entire federal government stops working.

Because the bills provide funding for government activities, in many instances they also dictate policy, i.e., which government activities get money, and which do not. That debate, often, disallows these bills’ passage before September 30th. When that happens, Congress uses a clever legislative tool called a “continuing resolution” or CR. At its core, a CR simply says that the government will remain open at its current funding levels. No federal agency or program is subject to any funding/policy decisions. None gets any new money, and none lose funding.