Twinning EB-5 with New Markets Tax Credits to Enhance Transaction Quality and Returns (Vol. 2, Issue 2, June 2014, Pages 21-23)

Twinning EB-5 with New Markets Tax Credits to Enhance Transaction Quality and Returns (Vol. 2, Issue 2, June 2014, Pages 21-23)

By Michael Fitzpatrick, Partner, Baker Tilly Virchow Krause, LLP

Recently, project sponsors have combined New Markets Tax Credits (NMTC) with EB-5 financing in order to provide additional capital to help close a funding gap and/or reduce the need for leverage, which has strengthened the overall financing structure of the projects. While significant benefits to project sponsors can be achieved, several structuring challenges need to be overcome.

NMTC Background

The NMTC program was enacted by the federal government in 2000 and is the first federal tax credit program to stimulate commercial investment in “low-income communities.” The program is overseen by the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund, an agency within the United States Department of Treasury. The CDFI Fund typically allocates $3.5 billion of NMTC authority to Community Development Entities (CDEs) on an annual basis. These CDEs monetize the tax credits, using the proceeds to provide subsidized financing to qualified commercial projects that promote positive community impact. Although different standards, NMTC-qualified areas will typically overlap EB-5 Targeted Employment Areas (TEA).

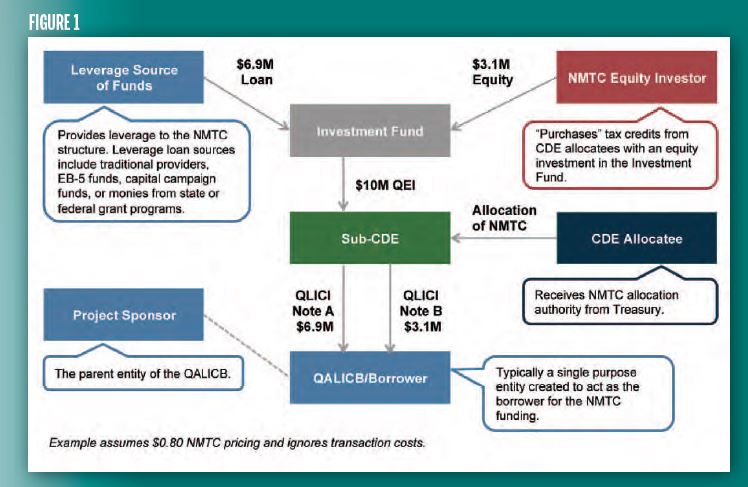

After typical transaction costs, NMTC can fund approximately 20 percent of the capital stack of a project. The NMTC-subsidized financing can be subordinated to EB-5 funding and is usually structured as interest-only debt with an annual cost of approximately three to four percent and a seven-year term to match the NMTC compliance period. NMTC rules require all sources of project funding to close simultaneously with the NMTC funding co-mingled in the NMTC structure (see figure 1), with non-NMTC sources of funds used as “NMTC leverage.” At the end of the seventh year, the transaction unwinds (see figure 4), resulting in most or all of the NMTC capital permanently remaining with the project sponsor.

Unlike EB-5, where a Regional Center may raise EB-5 funding at will, a finite amount of NMTC is allocated to CDEs each year from the CDFI Fund, and accessing it is very competitive. Less than 25 percent of the CDE applicants submitting an application for annual NMTC allocation authority are successful. Similarly, projects compete amongst each other for NMTC allocation from CDEs, as there are more projects seeking allocation than available. CDEs are free to allocate their limited NMTC resources to any qualified project within their service area that they deem worthy and are free to prioritize projects based on their business plan. A common element that all CDEs evaluate are the distress levels of the community and the projected community impact of the project, which is typically measured by job creation, the provision of unmet goods and services to the low-income community, environmentally sustainable outcomes, community support, and the potential for the project to be a catalyst for additional investment in the community. In addition, CDEs focus on financing impactful projects that are unable to obtain full funding through traditional sources of financing, making NMTC highly compatible with EB-5. Qualified projects must be located in low-income communities, which are defined by census tract information found using online mapping tools. Due to the complexity and economics of an NMTC transaction, projects with total costs of $6 million or more are most suitable.

Similarities of EB-5 and NMTC

A primary objective of both programs is to create jobs in distressed communities. While there are no specific job creation metrics for obtaining NMTC, providing evidence of job creation and other community benefits is important to persuading a CDE to allocate a portion of its NMTC to a project. In addition, both EB-5 and NMTC fund projects that have a gap in financing or are unable to fully fund with traditional sources of capital. Both programs provide underwriting that is more flexible than conventional financing and allows these projects to move forward. Additionally, NMTC can be used to cover costs that are ineligible under the EB-5 program, such as loan origination fees and construction period interest.

Transaction Structures

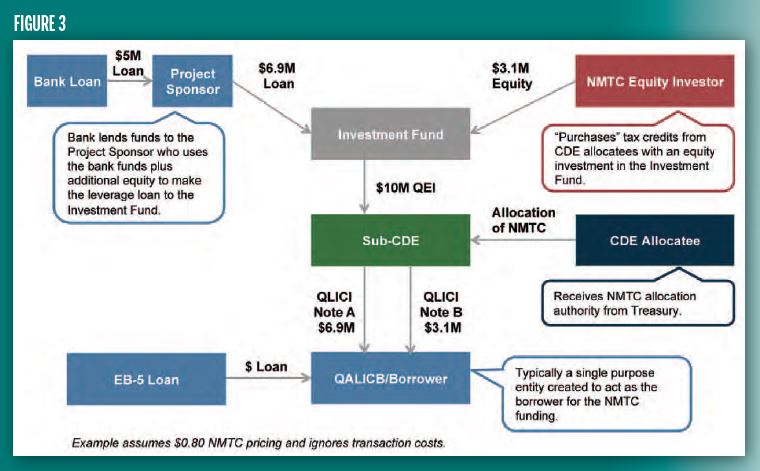

Structuring a transaction to be NMTC compliant requires some creativity to address the needs of all of the stakeholders. Figure 1 depicts a typical NMTC structure. In order for the tax credit generated by NMTC to flow to the party purchasing the tax credit, the “purchase price” is structured as an equity investment into a newly created “Investment Fund.” The Investment Fund is required to make a Qualified Equity Investment (QEI) in an amount equal to the amount of NMTC allocated by the CDE. Since the NMTC is 39 percent of the allocation amount, and purchased at a present-value discount, the Investment Fund needs additional capitalization from another source to fully fund the QEI; this additional capitalization is referred to as the “leverage loan.” The leverage loan can come from multiple sources and from any traditional source of project funding, including EB-5 monies. The QEI flows from the Investment Fund as an equity investment into a special-purpose entity formed for the specific project by the CDE (this entity is known as a subsidiary CDE or Sub-CDE). The Sub-CDE then makes a Qualified Low Income Community Investment (QLI-CI), which is typically depicted as an “A Note” [the source(s) of leverage] and a “B Note” (the NMTC proceeds, net of CDE fees).

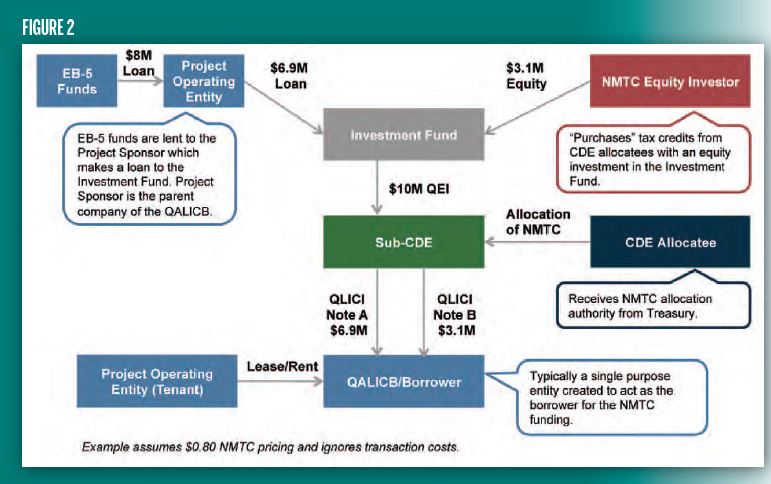

Figure 2 depicts a slight twist on the basic structure, where the EB-5 funds are structured as a loan to the operating entity of the project sponsor, which makes the leverage loan with the resulting QLICI flowing into a special purpose entity that will hold the real estate project and lease it to the operating company. In this example, the EB-5 project is a lender to the NMTC structure and a tenant of the Qualified Active Low Income Business (QALICB), where it can pledge a leasehold mortgage to secure the EB-5 loan.

Figure 3 depicts another variation where the sponsor funds the leverage using a bank loan and its own capital, with the resulting QLICI structured as subordinated debt with the EB-5 financing taking a first lien position.

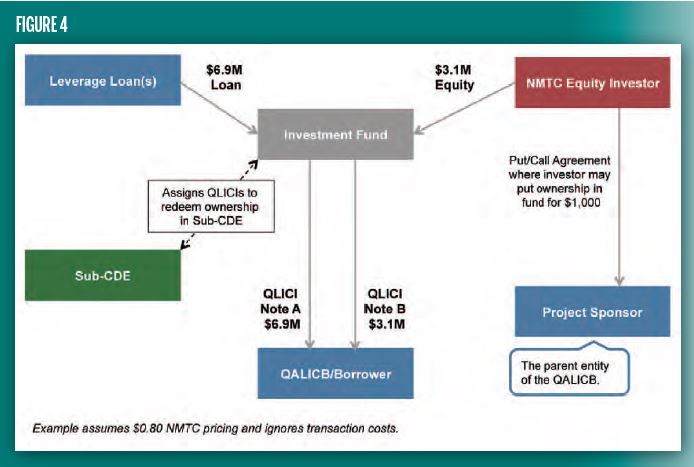

Figure 4 depicts the unwinding of the basic NMTC structure. At the completion of the seven-year compliance period, the unwinding will typically follow the process below:

- The Sub-CDE will distribute its assets (the A & B Notes) to the Investment Fund in exchange for the Investment Fund’s ownership in the Sub-CDE, resulting in no assets or equity remaining in the Sub-CDE. The Sub-CDE is eliminated from the structure.

- The Investment Fund now consists of the A & B Notes as its assets and loan(s) payable to the leverage source(s). At the original closing of the transaction, the project sponsor (or its designee) entered into Put & Call Agreements with the NMTC Investor. The Investor is expected to exercise its put and sell its ownership in the Investment Fund to the sponsor for a nominal amount (typically $1,000). The result is that a party related to the project owns the A and B Notes, with a corresponding note(s) payable to the leverage source(s).

- Typically, the project will refinance the QLICI A Note and repay the Investment Fund, which will use the proceeds to repay the leverage source(s), with the remaining B Note canceled for tax purposes since it is held by a related party. If the QALICB/Borrower is a for-profit entity, then the cancellation of the B-Note will have income tax ramifications that should be reviewed by a CPA.

Challenges of Twinning EB-5 and NMTC

Twinning the two programs comes with some challenges. The first challenge is the timing associated with the closing and drawing of funds. The NMTC program requires all sources of funds present at closing, as the QEI must be funded fully in cash at closing for the tax credits to flow to the investor. On the other hand, it is customary for EB-5 funds to be drawn from escrow as investors are approved by USCIS. Complicating this challenge is the difference in the investment horizon, where EB-5 terms are five years as a matter of market practice, while NMTC has a seven-year compliance period. With careful planning before the EB-5 offering is drafted, these challenges can be overcome with the use of bridge funding and/or creative transaction structuring.

An additional complication includes achieving the desired collateral position for the EB-5 investor, while also meeting the structuring requirements imposed in order to receive the NMTC tax opinion. While adding complication, early and careful planning with transaction professionals specializing in NMTC and EB-5 can result in achieving both objectives.

Successful Twinning of NMTC and EB-5

While twinning the programs does create some complication, numerous transactions have successfully used EB-5 and NMTC together to realize the full benefits of two powerful programs. The combination of the two incentives creates a stronger investment opportunity, benefiting the sponsor and EB-5 investor; however, it is important for a project to determine NMTC and EB-5 twinning feasibility early and to incorporate the proper structure and disclosures into its offering memorandum. ■

RCBJ Retrospective articles are reprinted from IIUSA’s Regional Center Business Journal trade magazine. Opinions expressed within these articles do not necessarily represent the views of IIUSA and are provided for educational purposes.